By Courtney Taylor

Dorothea Tanning’s (American, 1910–2012) Personne (Nobody) has proven to be one of the most popular pieces included in LSU Museum of Art’s exhibition Bonjour | Au Revoir Surréalisme. The book contains nine etchings each cut into three horizontal flaps that allow the head, torso, and trunk of a body to be recombined into a total of 729 figures—729 exquisite corpse figures.

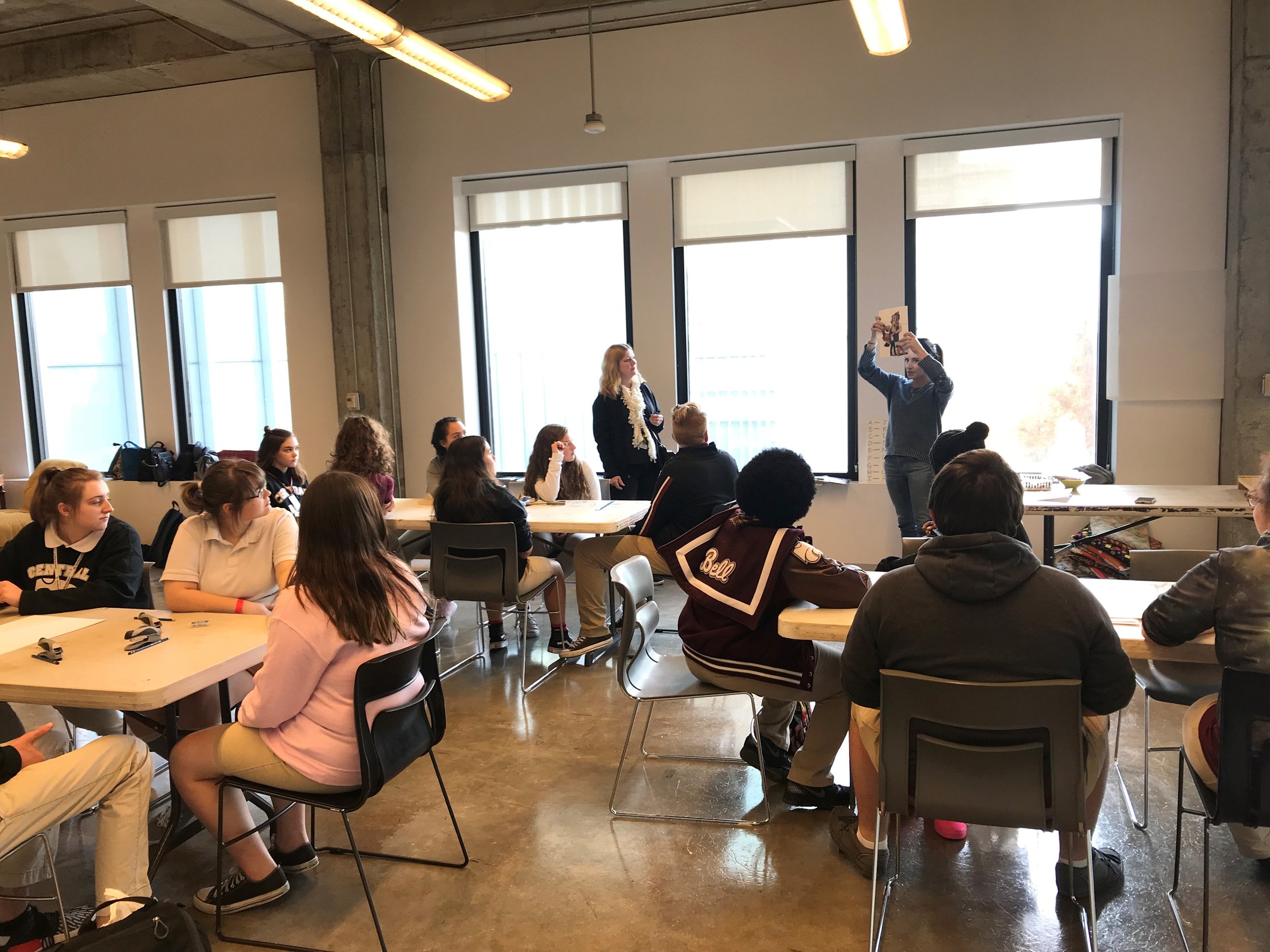

Tanning’s book is a variation on the well-known surrealist practice of playing exquisite corpse games. The idea was to add elements of play, chance, and collaboration by allowing each person to add an element, a word or body part for example, to a poem or drawing while concealing their addition before the next person added his or her element. The result was often absurd. In keeping the surrealist attempt to escape the confines of reason, Tanning attempted to access the play and imagination of childhood to escape logic. Tanning’s idea for cutting the books laterally came from books encountered in her own childhood. She said, “Personne is a grown-up’s fantasy.”[1] Students visiting the LSU Museum of Art’s exhibition have been challenged to create their own Personne-inspired collage exquisite corpse books.

Personne also bears the influence and expertise of master printer Georges Visat. All the works included in this exhibition were printed by Visat, whose specialty was printing and publishing books like Personne, which also includes texts by Lena Leclerq. Writing of her collaborations with Georges Visat, Tanning wrote: “With his virtuoso bag of tricks under control—his scumbles, varnishes, sugars, resists, spit, and resins, followed by hours of scrapings, polishings, inking, proofing…he brought out glorious deep-diving images in floated spectral colors for which other people got the credit.”[2] In the gallery, one may notice that all labels attribute the authorship to the artist who drew, painted or designed the plate from which the prints featured were created—but as Tanning points out the printer’s contributions cannot be underestimated.

Tanning expressed her own ambivalence around her printer’s contributions: “Constantly on the prowl for new techniques, Visat one day borrowed a little painting of mine and, by some latest method, made from it an etching. It was perfect.” “But was it wrong? Was it a fraud? Would a collector find it a cheat? Would Georges Visat with his special hands, his good natured genius, his light under a bushel of artists, reap opprobrium for keeping the flame of etching alive? As the years passed it became even harder to consign Visat to the caste of mere craftsmen, for he waded into editing, producing not only etchings but the whole book as well…such books were built, like cathedrals, with an inordinate amount of creative fervor and dedication”[3]

See the all the combinations of Tanning and Visat’s Personne here:

[1] Dorothea Tanning Foundation. Accessed 1.1.2018. https://www.dorotheatanning.org/life-and-work/view/512

[2] Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001) 242.

[3] Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001) 242.

Courtney Taylor is LSU MOA's curator.